My early years as a counselor were spent helping teenagers in a maximum-security juvenile detention center. As the years progressed, and no matter the severity of the crime, nearly every boy I sat across from had an inability to name his feelings. In my first session, I would give him a feelings chart—pictures of faces with expressions of various feelings and the respective feeling written under each face. Each client would use this feelings chart throughout our sessions to choose what he was feeling.

The reason this matters is quite powerful. If a young man has an inability to know what he is feeling, how could I expect him to know what his victim was feeling, and ultimately show remorse?

What’s more fascinating is that the understanding of emotion goes beyond those in detention centers. Take for instance a recent study where Google wanted to test their hiring process—a process focused primarily on hiring for hard skills: science, technology, engineering, and math.

To test if their hiring process was effective, they took their most productive teams at Google and studied the factors that made them successful. Surprisingly, the hard skills—the ones that we so often are concerned about as parents—came in dead last among those productive teams.

What came in at the top? Empathy, emotional intelligence, and at the top of the list was emotional safety. You can imagine how Google has changed its hiring process.[i]

Turns out that emotional awareness isn’t just effective for the remorse of juvenile delinquents or the success of teams in large companies. What we found in the research was surprising.

Emotions and Who Our Children Become

When Christi and I first became parents, we were overwhelmed by all of the books written on sleeping techniques, discipline strategies, parenting styles, and on and on—many of them contradicting one another. We were also surprised that, no matter what kind of parents people were or how successfully they raised their own kids, everybody (including those who never tried it) had an opinion on how to raise successful kids.

It quickly became all too complicated. To reduce my own fears and find out what really led to the outcomes we desired most in our kids, I went back to my counseling roots to find the answers.

After scouring the research, the one filter that cut through all of the parenting contradictions was emotional safety.

Though there are many more I list in chapter 3 of Safe House, consider that emotional safety is linked to children who:

- Have higher levels of self-esteem, self-worth, and self-competence[ii]

- Have higher academic skills, attitudes, and achievement[iii]

- Are more likely to enthusiastically engage in challenging tasks[iv]

- Later show higher levels of career commitment and performance[v]

- Are more likely to engage in more health-promoting behaviors, such as maintaining a healthy diet or engaging in exercise, and avoiding health-related risks, such as smoking, drinking, and drug abuse[vi]

- Are more likely to maintain faith in God, particularly if the parent adheres to the faith practices[vii]

- Have more satisfying romantic relationships in adulthood[viii]

I don’t know about you, but if these can be said of my kids, I will “have no greater joy” (3 John 4).

What Does the Bible Say About Feelings?

Just as God created our eyes, nose, skin, and bones, He also gave us feelings. Feelings are a way God speaks to us about people or situations. They tell us something about who we are and how we should interact with the people around us.

For example, Jesus told us to “love your neighbor as yourself” (Mark 12:31, CSB). But the prerequisite to this command is to love God with everything we have. John later describes it another way: “We love because he first loved us” (1 John 4:19, CSB). In other words, when I come to truly understand God’s love for me, the more I have in me to step into the shoes of my neighbor and love well.

But to love yourself requires that you’re humble and kind enough to yourself to understand what you’re feeling and why you’re feeling that way. The more you understand yourself in relation to His love for you, the easier it is to genuinely sit with and empathize with other people—being quick to listen, slow to speak, and slow to become angry (James 1:19).

Notice the Bible doesn’t say, “Don’t become angry.” Instead, it says to be slow to become angry and also not to sin in our anger (Ephesians 4:26).

In other words, a feeling is okay; it’s what we do with that feeling that matters.

Solomon sums it up best, “Patience is better than power, and controlling one’s emotions, than capturing a city” (Proverbs 16:32, CSB).

And that—teaching our kids to give their emotion a name and then decide what to do with it—is crucial to helping them love God and love others. This is where emotional and spiritual maturity go hand-in-hand: the lived out fruit of self-control (Galatians 5:23).

But it all starts with us as parents. Being emotionally safe with our kids provides calm to the fear center of their brain. The calmer our kids are in emotionally overwhelming situations, the more likely they are to think straight and make wise decisions.

This is also why the Bible tells us not to provoke our kids to anger, but to raise them up in the way of the Lord (Ephesians 6:4). When we’re angry, anxious, or emotionally overwhelmed, it’s much harder to think straight. I believe this is why Paul later writes to think on that which is noble and praiseworthy not until after he tells us to go to the Lord for our minds to be filled with peace (Phil. 4:6-8).

In a finite way, that’s our privilege as parents—to help our kids learn to name their feeling, make good decisions with that emotion, and begin to think about others. Not just the recipe for a great career and staying out of jail, but also one for living out the two greatest commandments.

Joshua Straub, Ph.D. is a husband, dad, and recovering human. By trade, Josh is a speaker, author, and family and leadership coach. A champion of human empathy, Josh leads Famous at Home, a company equipping leaders, organizations, military families, and churches in emotional intelligence and family wellness. Josh also is a Fellow of the Townsend Institute for Leadership and Counseling. As a marriage and family coach and consultant with The Straub Co. and professor of child psychology / crisis response, Josh coaches leaders to be famous at home so they can thrive on their stage. He also speaks regularly for Joint Special Operations Command and serves military families across the country.

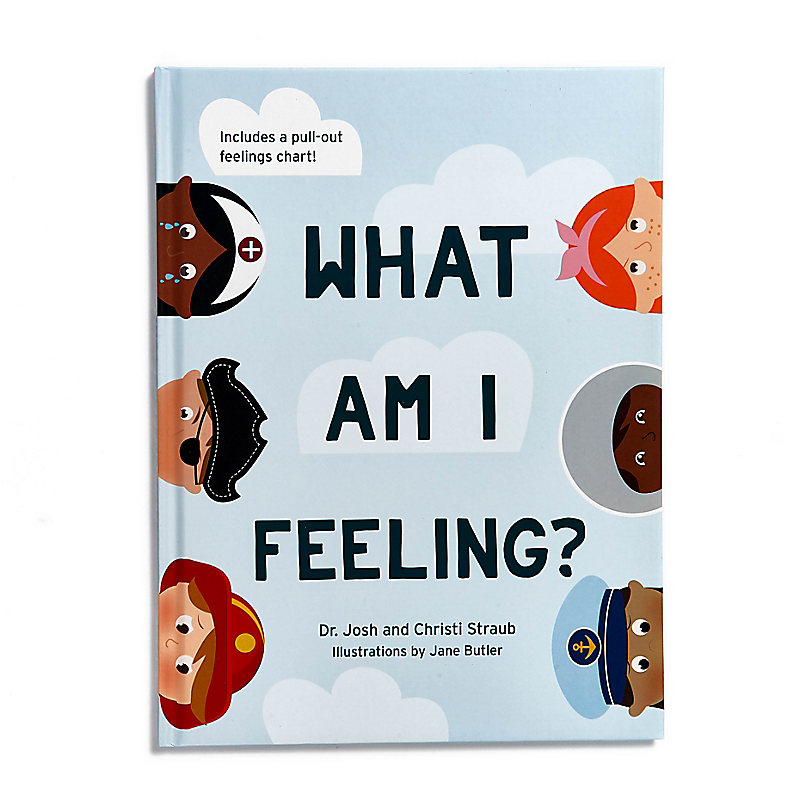

Josh is author/ coauthor of four books including Safe House: How Emotional Safety is the Key to Raising Kids Who Live, Love, and Lead Well and coauthor, along with his wife Christi, of their first children’s book called, What Am I Feeling? (B&H Kids, 2019). He and Christi also host the In This Together podcast, and in partnership with Lifeway Christian Resources, are the creators of TwentyTwoSix Parenting, a community of parents growing together to encourage the spiritual growth of their kids.

Most of all, Josh loves spending time with his wife, Christi, on the lake in their 1974 Crestliner, training their disobedient puppy, and watching their kids crush karaoke on a stage built in their dining room.

[i] https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2017/12/20/the-surprising-thing-google-learned-about-its-employees-and-what-it-means-for-todays-students/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.e82e1d40786f

[ii] This is found in more than 60 studies on the topic. The table of findings can be found in Mikulincer, M. & Shaver, P. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York, NY: The Guilford Press, p. 155-160.

[iii] Mikulincer, M. & Shaver, P. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York, NY: The Guilford Press, p. 237.

[iv] Matas, L., Arend, R., & Sroufe, L. A. (1978). Continuity of adaptation in the second year: The relationship between quality of attachment and later competence. Child Development, 49, 547-556.

[v] Blustein, D. L., Walbridge, M. M., Friedlander, M. L., & Palladino, D. E. (1991). Contributions of psychological separation and parental attachment to the career development process. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38, 39-50; Felsman, D. E. & Blustein, D. L. (1999). The role of peer relatedness in late adolescent career development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54, 279-295; and Scott, D. J. & Church, A. (2001). Separation/ attachment theory and career decidedness and commitment: Effects of parental divorce. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58, 328-347.

[vi] Huntsinger, E. T. & Luecken, L. J. (2004). Attachment relationships and health behavior: The meditational role of self-esteem. Psychology and Health, 19, 515-526 and Scharfe, E. & Eldredge, D. (2001). Associations between attachment representations and health behaviors in late adolescence. Journal of Health Psychology, 6, 295-307.

[vii] This is found in many studies. The seminal studies include Granqvist, P. (1998). Religiousness and perceived childhood attachment: On the question of compensation or correspondence. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 37, 350-367; Granqvist, P. & Hagekull, B. (1999). Religiousness and perceived childhood attachment: profiling socialized correspondence and emotional compensation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 36(2), 254-273; Kirkpatrick, L.A. & Shaver P.R. (1990). Attachment theory and religion: Childhood attachments, religious beliefs, and conversion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 29(3), 315-334; Granqvist, P. (2005). Building a bridge between attachment and religious coping: Tests of moderators and mediators. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 8(1), 35-47; and Powell, K. & Clark, C. (2011). Sticky faith: Everyday ideas to build lasting faith in your kids. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

[viii] Feeney, J. A., & Noller, P. (1990). Attachment style as a predictor of adult romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(2), 281-291; Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. R. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511–524; Hazan. C., & Shaver, P. R. (1990). Love and work: An attachment-theoretical perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 270-280; Heavey, C.L., Shenk, J.L. & Christensen, A. (1994). Marital conflict and divorce: A developmental family psychology perspective. Em L. L’Abate (Org.), Handbook of developmental family psychology and psychopathology (p. 221-242). New York: Wiley; Levy, M. B., & Davis, K. E. (1988). Love styles and attachment styles compared: Their relations to each other and to various relationship characteristics. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 5, 439-471; Simpson, J. A. (1990). Influence of attachment styles on romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 971–980.